David Freeman

(Photos)

When the crew of Dustoff 71 reported in to the 57th Medical Detachment’s Operations office for First Up duty on the evening of October 13, 1971, they checked the Mission Board and found one mission still pending from the afternoon shift.

CW2 Ron Schulz was the Aircraft Commander and WO1 John Chrin was the First Pilot. Schulz, with less than a month left in-country was preparing Chrin to take over as an Aircraft Commander. The crew that night also included crew chief Michael Darrah, and medic Hugo Gaytan. A third crewmember, Ricky Pate was along that evening because Michael Darrah was training him to become a crew chief.

The fact that a mission was still pending from earlier in the day bothered the Dustoff crew. Dustoff crews didn’t like to leave anyone in the field who was hurting. It was their job to get the injured out of the field and to a hospital as soon as possible. This guy had been out there too long. He had not been picked up earlier because of the weather. It was monsoon season, with rain and low clouds blanketing the area throughout the day, and the crew on duty during the day afternoon had not been able to make it in.

Schulz and his crew knew the weather could change, so they decided to go take a look. It was a unanimous decision. They all wanted to go. What none of them knew was that the intended patient had already died. This information was never transmitted back to Dustoff Operations because the patient was in a minefield and none of the South Vietnamese soldiers in the area was willing to go in to try to recover him. The fact that it was a Vietnamese patient did not deter the crew. Their mission included the medical evacuation of both Americans and Vietnamese, even North Vietnamese or VC if the occasion warranted it.

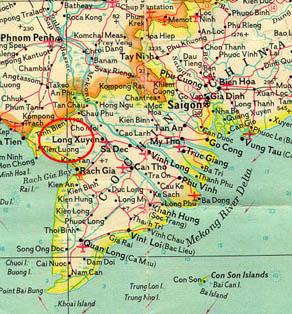

The location of this particular mission was in far western An Giang Province, not too far from the village of Chau Duc on the Cambodian Border and in an area known as the “Seven Sisters” mountains. These mountains are the only high areas in the part of South Vietnam, known as “the Delta”, or in military terms “IV Corps.” The four northernmost peaks that make up the Seven Sisters are in Cambodia. The three southernmost peaks are in South Vietnam. The highest of these is 2,330 feet high.

Departing Navy Binh Thuy, Schulz was encouraged by the weather. For the most part, the crew was able to remain clear of clouds. What clouds they did encounter were patchy and they soon flew through them, flying on instruments. Dustoff 71 contacted the Air Force radar controllers at nearby Air Force Binh Thuy (Paddy Control) and asked for radar vectors to the area of the intended pickup. The fact that it was growing dark was not really a concern, since the Dustoff crews routinely located ground troops at night and had worked out procedures to enable them to get into and out of their pickup sites in safely, even on very dark nights. (See the story Dustoffs at Night, if you are interested in the details of how this was done.)

As they reached the area south of the village of Chau Duc, Paddy advised the crew that radar contact had been lost. By this time, Schulz and his crew had established radio contact with troops on the ground who were attempting to provide some type of visual guidance to help the crew locate the pickup site. They were flying at 2,000 feet and were in and out of clouds, but hoped to soon establish visual contact because the ground troops were shooting up flares. When Paddy Control advised Dustoff 71 that he was no longer in radar contact, he advised him that the helicopter was at that time approximately seven miles from mountains. They were on a northwesterly heading, which Schulz apparently believed would keep them clear of the mountains, if they even went that far before establishing contact with the ground troops.

For reasons, we will never know, Schulz and his First Pilot, John Chrin, were apparently unaware that they had drifted south and were dangerously close to the 2,330 high peak known as Dop Chompa. While in radar contact with the ground troops, but prior to making visual contact, the helicopter impacted the side of the mountain at an approximate elevation of 2,000. It immediately burst into flames. The entire aircraft, except for the engine and tailboom, was consumed by the fire within a matter of minutes. The evidence examined during investigation indicated that all aboard died upon impact.

Jack Grass, “Dustoff 88” was on a standby status that night. Sometime between 10 or 11 PM Captain Aubrey Lange, the C.O. sent one of the operations enlisted men to wake Grass up. He told Grass that Dustoff 71 was missing and believed to have crashed in the mountains near Tri Tan. Lange wanted to fly to Tri Tan.

Lange and Grass departed Binh Thuy and headed west. They were to contact a ground unit at a field location east of Tri Tan. They immediately went IMC (instrument conditions) and picked up vectors from Paddy Control. It was turbulent, raining extremely hard, and scary. When they arrived in the approximate area, it was still raining very hard and still turbulent. The advisors on the ground told them they were approximately overhead and that it “sounded” like we were clear of the mountains by a couple miles. This was not a comforting factor for Grass and Lange. Grass asked the advisor if he had any vehicles/APCs available so he could circle the wagons to light up an area for them to land. As the helicopter circled overhead the ground forces got jeeps and APCs set up in a large circle with headlights shining into the center. Grass was still talking with Paddy Control who had them on the screen intermittently. He was pretty sure they were east of the mountains but was still nervous.

Grass started a slow circling descent with position lights on bright and the stowed landing light turned on. After what seemed an eternity the ground troops saw their light. They were probably at 6 or 7 hundred feet before they were spotted and, as luck would have it, they were directly above them. It wasn’t until the helicopter had descended below 3 hundred feet or so that they could make out the glow of lights below them. They landed in the center of the circle and shut down for the night.

Early the next morning at first light, Grass and Langer prepared to search the mountain just south of where Dustoff 71 was believed to have crashed. That is where ARVN ground troops reported seeing what they thought was a fire. They flew directly to the coordinates given and began their search. Jack Grass had a very strong feeling that they were nowhere near the crash sight and told that to Lange. He said just search the area grid by grid until they found the crash. Grass had very strong feelings that they would find the crash north their position. He told Lange that he was going to make one pass over the top of the mountain to their north, then he would go back to where they were previously searching. Jack believes he was “guided” to the site, as he found it almost immediately.

October 13 was my first day with the 57th Medical Detachment. I arrived late in the afternoon and never met any of the members of the crew that was lost that night. Consequently, the next morning, I was assigned to the Aircraft Accident Investigation team that would recover the bodies and try to determine what had happened.

The accident investigation team, along with members of Graves Registration (those charged with identifying and recovering remains) departed Navy Binh Thuy in two helicopters early the next morning enroute to Tri Tan, which was at the base of the mountain where the helicopter had crashed. The top of the mountain was obscured by clouds, so we had to wait until almost mid-morning before we could get to the crash site.

When we were able to fly up the side of the mountain, the advisor on board pointed out the wreckage to us. The jungle was very dense and all that could really be seen was a pile of ashes.

We approached and landed in a clearing on top of the mountain, where we were met by ARVN (Army of Vietnam) forces who led us down the side of the mountain to the scene of the crash.

When we arrived at the location where the aircraft had crashed, the Graves Registration team set to work immediately to recover the bodies. It was the consensus of opinion that the men had not lived long enough to know they had been burned, but had died upon impact. They were all in the approximate position that they would have occupied in the aircraft, except that the entire front part of the aircraft was totally gone. Only ashes remained. The front of the cockpit had smashed into a huge rock, a further indication that these men had died instantly.

There was something very puzzling about the crash site. As the morticians began moving the charred remains into body bags, they kept asking the C.O. how many people were on the aircraft. The answer was always the same. “Five.” They assured us that they had only found the remains of four people in the wreckage. We fanned out and began searching the dense jungle to locate the fifth person. At this time, we did not know who was missing.

Several hours of searching turned up nothing. Reluctantly, we moved back up to the top of the mountain, where the two choppers, who had already flown the recovered remains back to Binh Thuy, came back in to pick us up. By this time, it was late in the afternoon. We left with the assurance from the Special Forces advisor with the ARVNs that he and his men would find the fifth person. We flew back to Binh Thuy and they went back down the mountain to search.

out before dark.

Back at Binh Thuy, it was discovered that Mike Darrah was the one that was missing. This hit everybody hard, as he was a favorite of both the enlisted men and officers.

A few days later, we got word that Darrah had been found. He had apparently been thrown from the wreckage and was found several hundred yards down the side of the mountain from where the aircraft had impacted. At first we thought he might have survived the crash and tried to get away from the area, but the autopsy of the body indicated otherwise. Michael had apparently died from impact, as nearly all of the bones in his body were broken and there was severe trauma to his internal organs. We don’t know whether he was thrown out, or jumped, but we do know that the impact from either the crash or the fall, killed him.

1 comment